Batman is a rock-solid icon—and changes with the wind. From the 1930s “guy who punches everything” to the cheesy trivializations of the 1950s and the pop caricatures of the 1960s, to Miller’s epochal The Dark Knight Returns and the later movies, this supposedly consistent character has undergone major metamorphoses. What happened, why, and what’s cool about it?

In the course of the discussion, we touched upon a number of caped crusader flavors. Individual preferences were expressed; but a consensus soon emerged—that what makes Batman great is the multiplicity of ways in which he has been, and can be rendered. The Batman character transcends the editorial, story writing, and artistic styles of any given production team. I came away from this discussion believing (and still believe, today) that Batman is an essential piece of American folklore.

My ideas on the subject may be skewed a bit. Batman has been part of my reading experience since I was five years old. In the 2nd grade, my teacher felt it necessary to confiscate my class notebook, which contained blue and gray pencil sketches emulating the square jaw and flowing cowl of Dick Sprang’s Caped Crusader. Several years later, at age 10, I visited the DC Comics editorial offices for the first time. Bob Kane took time out from his labors at the drawing board to autograph a piece of original Batman panel art for me.

Batman in 1954, as rendered by Bill Finger and Dick Sprang, had an M.O. that almost perfectly matched my childhood fantasies and expectations. Not only was Batman the World’s Greatest Detective, identifying suspects with his Crime Computer and analyzing evidence with an electron microscope, but he also operated from a cave full of super-science bat vehicles. He could chase down lawbreakers on land, sea, and air with the Batmobile, the Batmarine, and the Batplane. My only complaint about the Batmobile was that it refused (at this point in history) to sprout wings on demand and take flight.

(Flying was the genetically-transmitted dream of all 1950s proto-science fiction fans. While other kids in the neighborhood dressed up in cowboy suits and shot at each other with cap pistols, we tossed cap rockets into the air, flew balsa wood model airplanes, and mailed in boxtops for space helmets. Flying was the only one-up, I thought, that that other Superhero really had going for him.)

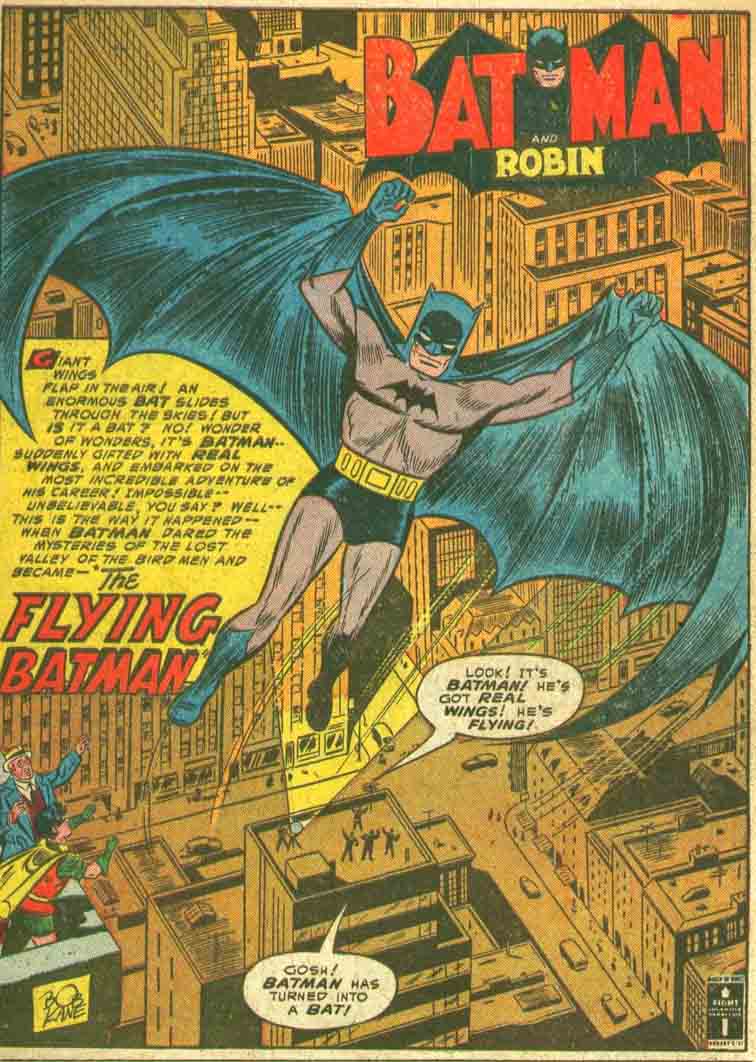

Imagine the thrill my eight-year old self experienced when the issue pictured left turned up in the comic book rack at my local candy store. Batman with wings! Those of you accustomed to 21st century versions of the character flying around at will, via jetpack, should understand this: in 1954, Batman with his own set of wings was an amazing, dreamlike concept. In 2nd grade art period, several of us attempted to overcome gravity by drawing the experimental flying cars described in My Weekly Reader and Junior Scholastic. Things like this and this confirmed to me that the DC Comics creative staff were kindred spirits. (To browse through a whole bunch more Bat-covers, click here. You don’t have to limit yourself to my childhood golden era. Come back when you’re ready for more Bat-talk.)

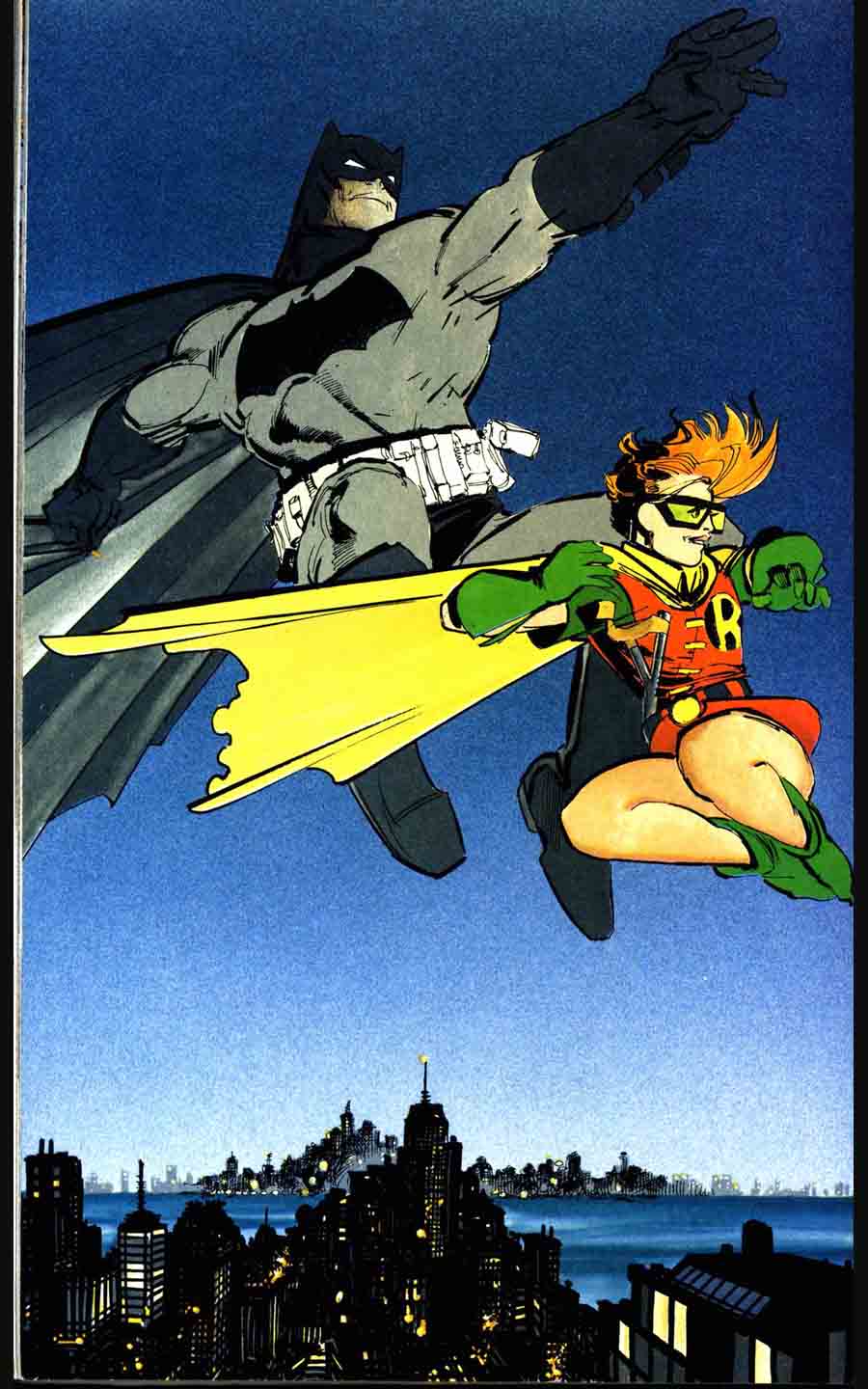

So what did happen to Batman after the cheesy trivializations of the late 1950s and early ’60s (Bathound, Bat-Mite, dinosaur fights); and what was cool about it? A dedicated scholar might be tempted to expand the list of Batman flavors included in Teresa’s excellent Minicon panel précis: Frank Miller’s Dark Knight owes something to the long-eared Night Ghost created by Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams (and taken up by Jim Aparo). In turn, Bruce Timm, Alan Burnett, and Paul Dini lightened Miller’s Dark Knight, creating several new flavors of Batman in the DC animated world.

And what are we to make of the version from the 1960s TV show, described and idealized by James Beard? (At the least, Tim Burton was influenced by this Batman with respect to costume design for his live-action movies.)

Ten years ago, when we held our Batman discussion at Minicon, I found myself in a bit of dialectic opposition to Teresa Nielsen Hayden (never really a very enviable position to be in). Teresa countered my nostalgia for the “Fair Universe” Batman of my childhood by pointing out that the universe isn’t actually fair. For Teresa, the avenging juggernaut of a caped crusader

Looking toward the commoners’ section of Megatheopolis, Jarles was reminded of pictures he had seen of the cities of the Black Ages, or Middle Ages—or whatever that period of the Dawn Civilization had been called.

Fritz Leiber, Gather Darkness

Fans of Frank Miller’s vision should certainly find echoes of that vision in Fritz Leiber’s work:

But every power-crazy, people-despising dictatorship breeds its own revolution. In the society of Megatheopolis, the revolutionaries use the scientific knowledge which they have obtained from renegade priests and from self-taught scientists among the people to create a counter-religion based upon curious modifications of the ancient cult of Satanism. The revolutionaries live in cellars, sewers, abandoned buildings and tunnels (forgotten subways?) and, of course, have their spies within the ruling priesthood, itself.

Gather Darkness

If you place Frank Miller’s Batman in a melting pot: add a cup of Neal Adams’ Night Ghost, mix in a few tablespoons of the somersaulting World’s Greatest Detective, and sift this through the roots of classic American short story writers (O.Henry, Bret Harte, maybe even a bit of early Kurt Vonnegut), then you can begin to approximate the contribution to the Batman gestalt made by Bruce Timm in the 1990s. Out of Timm’s melting pot comes Batman: The Animated Series and The New Batman Adventures. Like Grant Morrison in present-day DC comic books, Bruce Timm is fully cognizant of the entire history of the character. With help from collaborators Alan Burnett, Paul Dini, and Darwyn Cooke, the Timm-animated Batman pays tribute to the great creators in Batman’s history. The DCAU (DC Animated Universe) team puts the steel-jawed crusader into a Gotham cityscape inspired by the 1989 live-action movie. The Timm Batman operates in the “City of Night,” but this city is a bit less dreadful than Frank Miller’s or Fritz Leiber’s. Their Batman has an element of gothic romance that Miller’s lacks: I am Vengeance, I am the Night!”

Bruce Timm’s animation style contains hints of many classic comic book artists, from the Max Fleischer animators (pictured right) in Paramount’s 1940s Superman to character caricatures in the tradition of MAD Magazine’s Willie Elder. But, for me, the outstanding characteristic of Batman: TAS is its fine, tight writing and plotting. Batman: TAS and its successor (The New Adventures) contain the finest storytelling you can find in any version of Batman. In these stories, Batman is always a significant character. But, wisely, the writers don’t always make him the central character of the story.

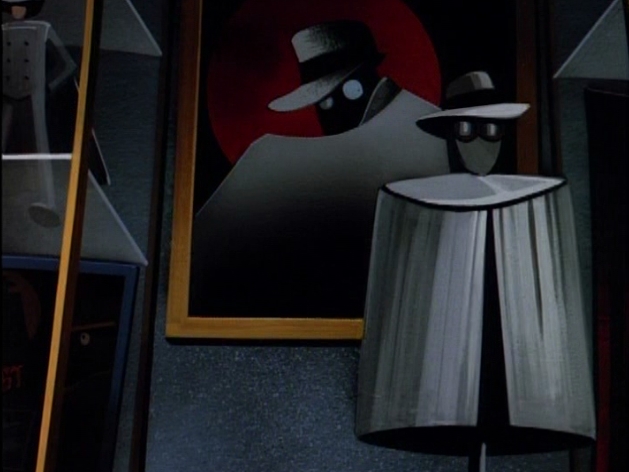

Op cit: Batman TAS episode 18, “Beware the Gray Ghost,” focuses on the career and subsequent decline of TV actor Simon Trent. The episode opens with young Bruce Wayne eagerly following the Gray Ghost’s adventures on the family TV set. It then cuts to the present day (1992), where Batman is investigating a series of bombings. The bombings bear a strong resemblance to the fictional “Mad Bomber” episode of The Gray Ghost that Bruce saw as a child. We see Trent living alone in a small apartment—surrounded by Gray Ghost memorabilia and rejected for new parts—due to the typecasting of his early career. In despair, Trent trashes his apartment and sells his Gray Ghost memorabilia to a toy store. After falling asleep, he wakes up to find his Gray Ghost costume returned—with an attached note from Batman asking for help. Trent meets with Batman and is, at first, reluctant to offer any help. But when Batman subsequently finds himself in a cul-de-sac, you can guess what happens.

After Batman and Trent combine to track down and apprehend the “real life” bomber, Batman shows Trent a special corner of the Batcave. The Gray Ghost merchandise Bruce collected as a child is on permanent display there. (Pictured right.) A Batman For

Every Season by Lenny Bailes

The voice actor who played the Gray Ghost in this episode is Adam West. The episode was specifically produced by Bruce Timm as a tribute to West.

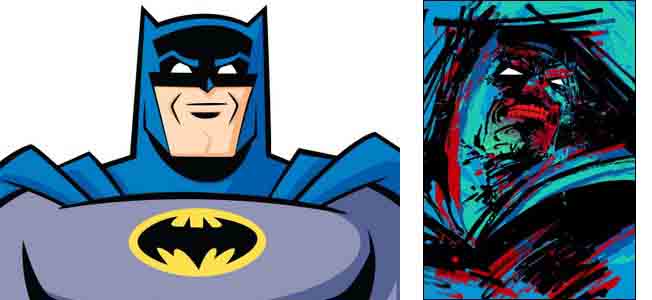

Gray Ghost notwithstanding, I find myself unable to resonate with the concept of Adam West’s Batman as the truest and best version of the character. It’s hard to dispute Teresa’s notion that a “boy scout” Batman is less interesting than the Miller one from the “City of Dreadful Night.” (The two bat-images linked in this paragraph are both from the Warren Ellis creation: Planetary: Night on Earth (2003), where Ellis plays with the notion of Batman actually shifting between alternate versions of himself in real time.)

To be fair to James Beard’s thesis that Batman ’66 is the Batman we should all follow, my reading is that James freely cites elements from the TV series and early ’50s comic books, the work of Chuck Dixon in Detective Comics, and the DC Animated Universe to put forth the idea that Batman is a good-natured, square shooting guy who always wins. The question that might be asked is whether Batman always prevails because his heart is pure, or because he’s smarter and more resourceful than anyone else in the world. Bruce Timm, Paul Dini, and Stan Berkowitz reinforce at least the “smarter and more resourceful” part of this in their treatment of Batman for the Justice League and Justice League Unlimited animated episodes. Their JLU Batman is a bit tougher and smarter than he was in the solo adventures—possibly because he has to be to hang with the ramped-up heroes and super-villains on the JLU turf. (As voiced by the wonderful Kevin Conroy, the JLU Batman is also a crooner.)

In our Minicon discussion on this topic, Neil Gaiman cited his own ultimate exemplar of Batman: a story where the caped crusader has been submerged below the surface in a pit of quicksand. For any other mortal man that would have been the end. But this is Batman! Presently, two arms shoot back above the surface of the quicksand and an indomitable, indefatigible figure extricates himself from the pit.

The “good-natured, square shooting” Batman finds his most recent representation in the children’s TV series Batman: The Brave and the Bold. This series seems to have been dually targeted, at an 8-to-10- year-old audience and at their DCAU-addicted parents. Batman, here, is not unlike the square-jawed Bill Finger/Dick Sprang (or Sheldon Moldoff) version from 1954. We discover that Batman is best friends with everyone who’s anyone from the last 50 years of DC Comics. I liked watching it! Every episode didn’t keep me on the edge of my seat, but I enjoyed seeing Bat-Mite answer a disgruntled fan (and moderate the DC editorial staff) at a 5th-dimensional comic convention.

I’m not going to forget Neil Gaiman’s vision of Batman. It may be the most lasting one. In my last ten years of life in the United States, I’ve wished several times that that guy who can extricate himself from quicksand pits (or go up against a combination of Superman, Luthor, and Brainiac) was real.

Lenny Bailes is a longtime science fiction fan, who helps put on small science fiction literary conventions and even still publishes a fanzine. IT specialist by day and college instructor by night, he desperately tries to find time for other reading, writing, and music-making.

5 Comments